When users start using a product, they have certain expectations of how the product should work, for example, where specific controls are located in an interface or what steps to take to order an item. These expectations are known as the mental model. We will see in this article the importance of these mental models and how they can help us, as a designer, to design a user-friendly product.

What is a mental model?

Un mental model is the set of perceptions and beliefs a user may have about how something works. It can be about a car or a website. This model is built primarily on the person's past experiences.

The concept of mental models comes from the book by Scottish psychologist, Kenneth Craik, entitled “The Nature of Exploration”. He said the mind builds small-scale reality models to anticipate and explain events.

An example in web interfaces is the burger menu, an icon made up of three lines stacked on top of each other. When clicked, it usually opens a navigation menu. The mental model of the user facing this icon is: “I have to click on this menu to see all the different sections/pages of this site/application”.

Another example, it is not uncommon to see children interacting easily with touchscreen devices, even if they are not familiar with the device. It's not because they spent time learning how to use each individual device, but because they got to know one in particular and how it works. Their brain has stored a mental model for an operation, and they are able to successfully apply it to other devices using similar patterns and sequences. The mental model is therefore not a static creation, it is able to evolve. It is influenced by new experiences with the product, other technologies and everyday life.

An important point, these mental models are very anchored in the individual. The Jacob's law, established by Jakob nielsen, the inventor of “usability engineering” and a founding member of the Nielsen Norman Group, states that “users spend most of their time on websites other than your own.” In other words, users expect your site to work the same as every other site they already know. This means that people learn conventions and, based on experience, they expect things to work a certain way. The more these conventions become established, the more difficult it is to change these mental models.

Beware of your own mental models

As designers, we have our own mental models, acquired over the course of our projects, through our design achievements or by exchanging with other designers. We can then fall into the trap of the “designer bubble” and thus design something that makes sense to us and other designers, but which may still confuse the average user. This type of disconnection creates usability issues, as the product does not match user expectations and existing knowledge. We are in the case where our mental models and those of the user are not aligned and that can be catastrophic.

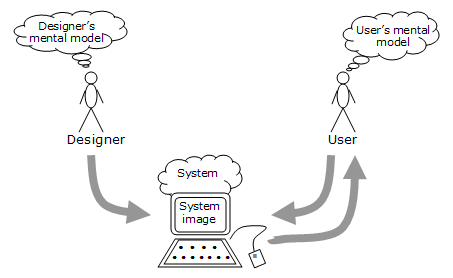

Don Norman, the other founding member of the Nielsen Norman group and the author of the famous book The Design of Everyday Things (1988), explains the phenomenon well:

“One of the great usability dilemmas is the common gap between the mental models of designers and those of users. […] The problem of ensuring that the mental model of the user matches the model of the designer arises because the designer does not speak directly with the user. The designer can only talk to the user through the “system image” – the designer's materialized mental model. The system image is, like text, open to interpretation.”

Image that illustrates the words of Donald Norman in his book “The Design of Everyday Things”

The history of web interfaces is littered with examples of misalignment, which ultimately resulted in adjustments to ultimately align.

For example, most shoppers on e-commerce sites expect optional registration and prefer not to spend their time filling out forms, but paying as a guest. This is a consequence of the explosion of e-commerce and the previous experiences of these Internet users.

In another example, between late 2017 and mid-2018, Snapchat lost 3 million users due to a new interface that fell far short of user expectations. The existing mental models did not match the new version and in the end, users wanted Snapchat to look and function like the previous version. They were confused, felt incompetent and this change led to a mass exodus. A petition was even signed by more than a million users and Snapchat carried out a redesign by putting back old features.

To recap, people have expectations and mental models based on past experiences of using a specific product. Unexpected surprises in the UX or UI can lead to confusion and frustration and businesses pay the price.

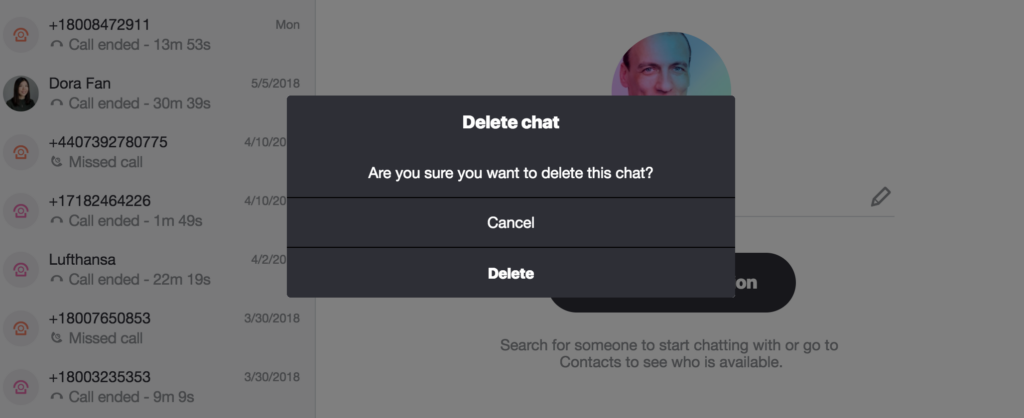

Another mismatch of mental models in action:

Skype had confused its users by offering dialogs where the options did not look like standard dialog buttons.

How to identify the mental models of the user?

Although mental models are unique to each individual, it is possible to discover common patterns among your users. Identifying them early in your project will increase your chances of designing an easy-to-use, high-performance product. The best way to do this is to use user research methods such as:

- usability testing

- user observation

- interviews

- card sorting

This is a fairly extensive and necessary research because what we seek to reveal are the motivations, the thought processes and the emotional state of the users.

Mental models in UX design

How to design the most user-friendly product that takes into account the mental models of the user? We can offer the user three different experiences, three design strategies, depending on whether or not we align with the user's mental models:

1. Known Experience

Based on Jakob's law of the user's mental models, the experience offered here will be the closest to what he already knows. We align ourselves with our mental models, we don't reinvent the wheel, we try to make the experience as natural as possible. A few ways to achieve this:

● Perform advanced user research: before showing the interfaces, ask the user to explain to you the steps they took to accomplish the task. Observe what he is doing right now to achieve those goals, without your product. Base your userflow on patterns derived from what your customers are already doing.

● Adapt the terminology to your user: understand your user's language. Don't invent new formulations that mean nothing to them. UX writing is important. Find words that sound familiar. This helps your product to be instantly recognizable.

● Take inspiration from the interface models that the user already uses: how is the experience structured? What products does this customer use on a daily basis? What types of interfaces are appropriate to the context of your product?

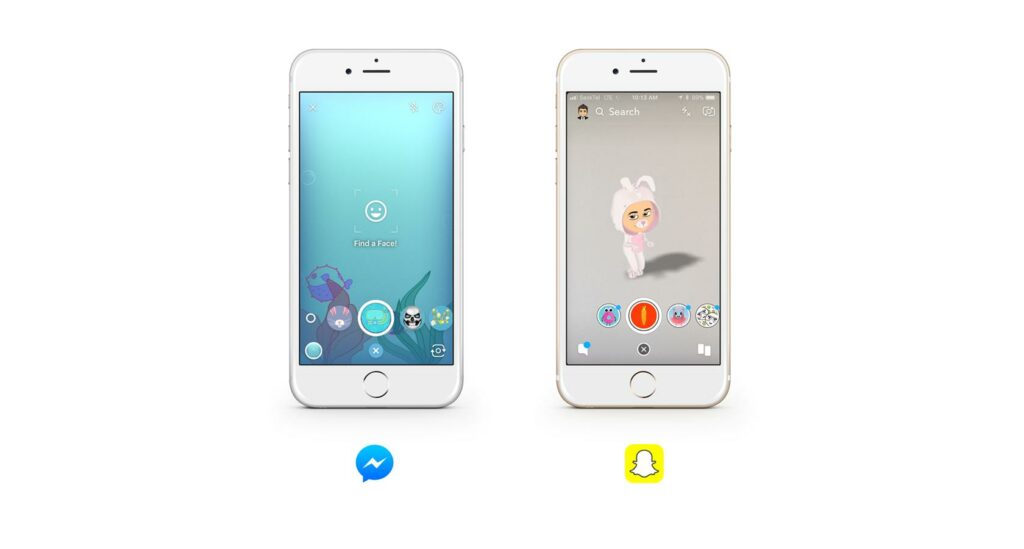

We can thus sometimes approach a true copy of an interface. An example is Facebook Messenger's user interface which has taken over that of Snapchat, capitalizing on existing mental models. Users of one popular app will have no trouble using and enjoying the other. This copy of functionality if it is assumed and well anchored in the heads of users will not interfere if your final product still meets a need.

2. The familiar experience

For the sake of innovation and differentiation, it is sometimes necessary to offer a slightly different interface or product. We must then move away somewhat from the mental models of our user. There are several ways to offer the user a different but familiar experience because we stay close to their mental models:

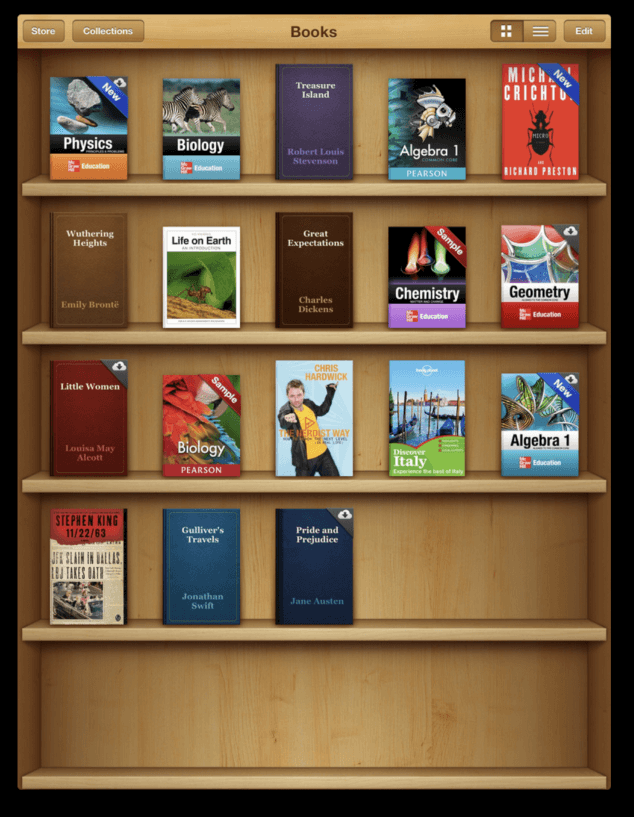

● Use skeuomorphism: it is the principle that mimics the interaction and appearance of a real object. A human brain connects what it sees in the user interface and its past experience, whether real or digital. Remember the first user interfaces of books, music players or notepads, you could find this on older versions of iOS. When users of this OS first saw Apple Books, they thought, "Okay, that looks like a physical bookshelf, so I should probably pick up the book." ”

Apple Books app

● Draw inspiration from the natural world: without doing biomimicry, a copy of elements found in nature necessarily brings familiarity and comfort to human beings. For example, Google's Material Design system is inspired by the physical world and its textures. The elements of light, shadow and physical matter (for the majority) are universally experienced.

● Use “perceived affordances”: explore different techniques to visually suggest the function of the model and how it should be used. We can unconsciously recognize the function of a mug just by looking at it. The shape suggests it could hold something, and its size indicates it can be held with one hand.

The car seat adjustment in a Mercedes is a prime example of the use of perceived affordance. A car seat shape for the controls intuitively makes it easier to understand and use the system.

An example that brings together all these notions is the mental model of volume sliders. This model is inspired by physical buttons, those “knobs” found on hi-fi systems or sound mixers.

In the example above, the left slider represents the mental model that most people would have for a volume slider. The middle slider was meant as a joke, but it illustrates an important point. The slider completely contradicts the mental models and expectations of users, as it looks like a vertical slider, but instead it works horizontally. The slider on the right is taken from Apple's iOS. Apple has used creativity and innovation to design something new and original, but it still respects the latticework of mental models that forms the shared expectation of how a volume slider works.

3. The unique experience

The trickiest case. How to pass a totally innovative feature that may be against the mental model of the user? One of the answers can be provided by Robert Greene:

“Everyone understands the need for change in the abstract, but people are creatures of habit. Too much innovation is traumatic and will lead to revolt…respect the old way of doing things. If a change is needed, make it feel like a slight improvement over the past.”

Solutions to this radical change:

● Break down the new concept into several steps: keep an end goal in mind, but break it down into thoughtful steps to gradually influence the user's mental model. Imagine we have a new model of driverless car that no longer needs a steering wheel. In 2019, completely removing the steering wheel will be too sudden a change. Instead, we should be able to hide the steering wheel when it's not needed, but it's still there. Once people have a better acceptance of this concept, the steering wheel can be completely removed.

● Offer tutorials and guided paths: show the user how the product could be used through effective onboarding and marketing. Realign their mental model through education. Use product videos to showcase your new concept.

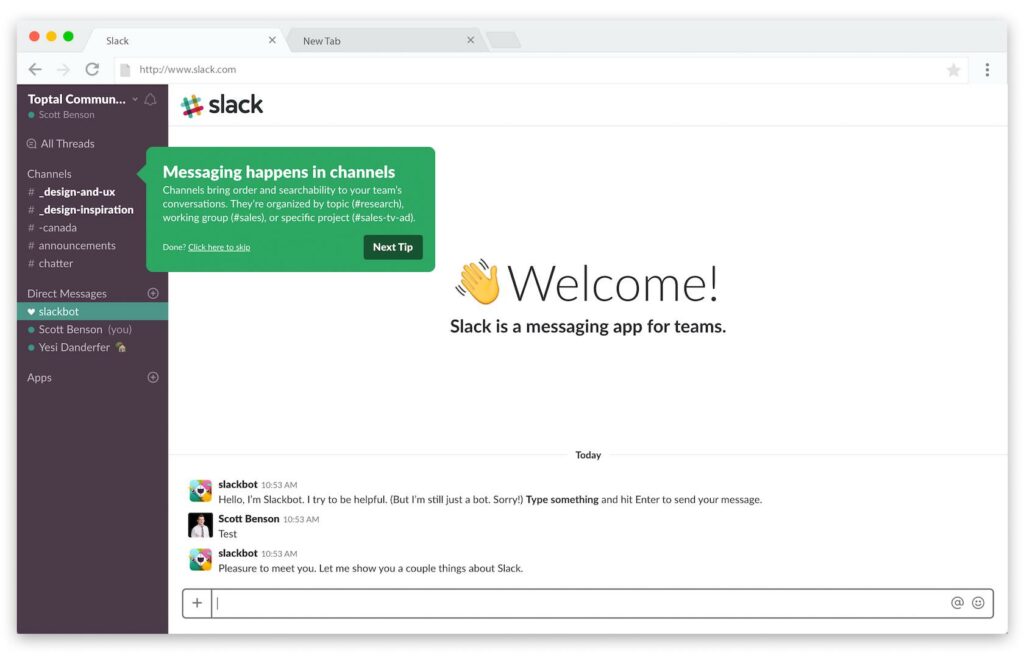

Slack uses interactive tours to help new users learn the interface and effectively improve any conflicting mental models users may have.

● Take into account the user's learning curve: to support the user in your innovation, you have to take into account his motivation. He always has to find an interest in it. It is therefore essential to have a product that inspires and to respect the user's learning curve. This usually takes time. The example of Gmail which offers the user to test the new interface without imposing it is a good example.

● Wait for the arrival of a pioneer: opportunistic and not really ideal solution. Ideas are often ahead of their time. Sometimes you need a trailblazer to prepare the user's mental model for new conceptual models to come. “Those who finish a revolution are rarely those who start it.”

An example, in 2012, Google Glass was a breakthrough technology, but it failed to catch on. Users couldn't figure out how to integrate it into their lives. Google probably launched it knowing it wouldn't be a hit with consumers. However, it started our thoughts on the possibilities of the future.

I hope these different approaches to mental models have enlightened you and will help you in the next UX design of your interfaces, with the aim of more usability and comfort for your users 😉

Sources

– Mental Models – Donald Normanhttps://www.interaction-design.org/literature/book/the-glossary-of-human-

computer-interaction/mental-models

– Leveraging Mental Models in UX Design – Scott Bensonhttps://www.toptal.com/designers/ux/mental-models-ux-design

– Understanding mental and conceptual models in product design – Alana Brajdic

https://uxdesign.cc/understanding-mental-and-conceptual-models-in-prod uct-design-7d69de3cae26

Damien DUCA, UI-UX Designer @UX-Republic

Image sources: https://undraw.co/illustrations

Our next trainings

UX-DESIGN: THE FUNDAMENTALS # Paris

SMILE Paris

163 quay of Doctor Dervaux 92600 Asnières-sur-Seine

VISUAL THINKING: CONCRETE YOUR IDEAS # Paris

UX-REPUBLIC Paris

11 rue de Rome - 75008 Paris

DIGITAL ACCESSIBILITY AWARENESS #Paris

SMILE Paris

163 quay of Doctor Dervaux 92600 Asnières-sur-Seine

DIGITAL ACCESSIBILITY AWARENESS #Belgium

UX-REPUBLIC Belgium

12 avenue de Broqueville - 1150 Woluwe-Saint-Pierre

ACCESSIBLE UX/UI DESIGN # Paris

SMILE Paris

163 quay of Doctor Dervaux 92600 Asnières-sur-Seine

AWARENESS OF DIGITAL ECO-DESIGN # Belgium

UX-REPUBLIC Belgium

12 avenue de Broqueville - 1150 Woluwe-Saint-Pierre

STORYTELLING: THE ART OF CONVINCING # Paris

SMILE Paris

163 quay of Doctor Dervaux 92600 Asnières-sur-Seine

UX/UI ECO-DESIGN # Paris

SMILE Paris

163 quay of Doctor Dervaux 92600 Asnières-sur-Seine

DESIGN THINKING: CREATING INNOVATION # Belgium

UX-REPUBLIC Belgium

12 avenue de Broqueville - 1150 Woluwe-Saint-Pierre